Remember me whining about how I couldn’t case the sausages I was making? Well, that is a problem no longer. My indulgent husband went with me to our local Academy store “just to look” at the sausage stuffer they sell there. We examined it, decided it would work for what we wanted to do, then went home and researched it. Within a few days of me waffling around, he finally decided we were just going to buy it, and we had ourselves one shiny new 5-pound LEM sausage stuffer.

And why start with a nice easy sausage to stuff? Where would be the challenge in that? For this next experiment, we decided to try an emulsified sausage, in our case Kielbasa (again, courtesy of Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking, and Curing

We started the process by dicing up and partially freezing pork back fat and beef stew meat. These were sent through the large die on the grinder.

This was returned to the freezer (it’s important for the sausage to stay very cold throughout the process so that the emulsion is not “broken”) till not quite frozen. This was mixed with salt, pink salt, sugar, and crushed ice and sent through the small die of the grinder.

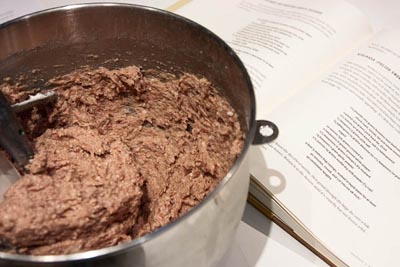

By this point, the mixture was already looking fairly uniform, but to make the actual emulsion, these ground meat mixture, a variety of kielbasa spices, and powdered milk (to help the sausage retain its moisture through the cooking process) were mixed vigorously in a KitchenAid mixer.

Then, finally, we got to use our stuffer. Several small lengths of hog casing were fed onto the stuffing horn and the now very pasty kielbasa mixture was loaded into the stuffer’s canister. Sean helped regulate the casings’ fill rate while I worked the crank, slowly compressing the sausage in the canister and forcing it out the horn. It was beautiful. Before long, we had three lengths of beautiful raw kielbasa.

I liked the LEM stuffer. It has metal on metal gearing and a pressure relief valve. Plus, for our needs, anything larger than a 5-pound capacity stuffer was sort of silly. The LEM’s piston and o-ring assembly fit very nicely into the canister – there was no leakage as we were using the device. The cranking was effortless and operation was very smooth. I haven’t used any other sausage stuffers (outside the ill-fated KitchenAid stuffer attachment), so I cannot comment on them comparatively. But thus far, I’m very happy with our purchase. Here’s the link: LEM Products 5 - lb. Vertical Stainless Steel Sausage Stuffer

We let these sausages dry in the refrigerator for a day (because smoke adheres better to a nice tacky surface), and then fired up the smoker. We had purchased some peach wood from a farm stand between Fredericksburg and Austin, and I had lopped off several chunks of this for our smoking project. I soaked them for a couple hours and then drained them before adding them to the hot coals of the smoker. The chunks worked much better than the chips I had tried last time.

I still can’t really regulate the temperature. For one, I don’t have a good way to measure it yet. The factory thermometer on our smoker gives a range for “Ideal,” it doesn’t share the actual temperature. Consequently, I only had these sausages on the smoker for maybe 35-45 minutes before they had reached their final internal temperature and needed to be removed from the smoker.

How did they taste? Well, not quite like I expected, to be honest. The texture was great. Our emulsion definitely held. The taste wasn’t bad per se, but the kielbasa was definitely too salty. I think I need a scale that’s more adept at measuring small amounts than my current kitchen scale.

Also, while I used the quantities of meat and fat and other ingredients specified, my yield was substantially less than expected. I wound up with three roughly 12-ounce sausage rings that were roughly 15-inches in length. I should have been able to fill six 18-inch casings. Maybe the hog from which our casings came had fatter innards than Ruhlman and Polcyn’s. Or, maybe we overstuffed them. Either way, it was a fun project – one we’re likely to repeat again soon.

This is the next step in our journey toward curing our own sausages. I’ve been looking into expanding our library beyond the much loved Charcuterie text. Hank Shaw of Hunter Angler Gardener Cook fame has an excellent listing of books in his charcuterie library. All the books he lists sound quite interesting, but the ones I think I’m most leaning toward are: The Art of Making Fermented Sausages